The Flight

Early on the morning of Thursday 30th September 1954, Flight Lieutenant Arthur Gavan at No.2 ANS, RAF Thorney Island gave a briefing for a navigational training sortie to take place later that morning. Gavan was the Duty Flight Commander on Varsity Squadron, and he duly authorised Sergeant HPS Fowler to fly Marathon s/n XA271/A on a cross-country exercise routing from Thorney Island to Cosham and then via Bude – Trowbridge – Northampton – Spalding – Dungeness – Petersfield and back to base. The exercise was to proceed at the nearest quadrantal heights to 6/7,000 feet.

At 9.44am (08:44 hrs Zulu/GMT) Sgt Fowler eased the Marathon away from Thorney Island’s runway, and using radio callsign ‘Cannibal Dog Mike’, set course for Cosham and on westward to Bude. Aboard he had a crew of staff navigator, two pupils and a passenger. The full crew was as follows:

Sgt Henry PS Fowler (Pilot)

P Off James Henry Hurlstone Green (Staff Navigator)

Fg Off Eric Arthur Dench (Student Navigator)

P Off Sumair Persad (Student Navigator)

Sgt Gordon HE Davies (Air Gunner - passenger)

The Bude leg was completed without incident, but at 5,000 feet, rather than the briefed 7,000 feet. The aircraft then turned onto the Trowbridge leg at the same altitude and at 11.30am XA271 was recorded 30 miles southwest of Trowbridge. At this time, Sgt Fowler passed a QDM (magnetic heading to station) of 125 degrees to Thorney Island tower, and this was returned to the aircraft as 296 degrees true. Fowler had meantime changed course towards Northampton. A position line obtained at 11.40am by P Off Green showed the aircraft’s position to be two miles south of Trowbridge.

At 11.45am that morning, about two hours after taking off from Thorney Island the aircraft was heard making an unusual noise in cloud. Immediately after this it was seen in a left-turning dive at about 300 feet, with both outer wings missing (the outer wings were estimated to have broken off at about 1,000 feet). The Marathon pulled out of the dive at a very low height and went into a steep climb, by which time it was heading in a south-westerly direction. At the top of this climb it levelled out for a short period and then dropped onto its starboard side, turned right and dived into the ground. The aircraft was apparently in and out of low cloud during the latter part of its flight following detachment of the outer wings. It struck the ground in a steep nose-down attitude and all five occupants were killed. It was later reported in the local press that a partially-opened parachute had been seen attached to one of the bodies, indicating that at least one person might have tried to make an escape. There is no evidence of this in the official records.

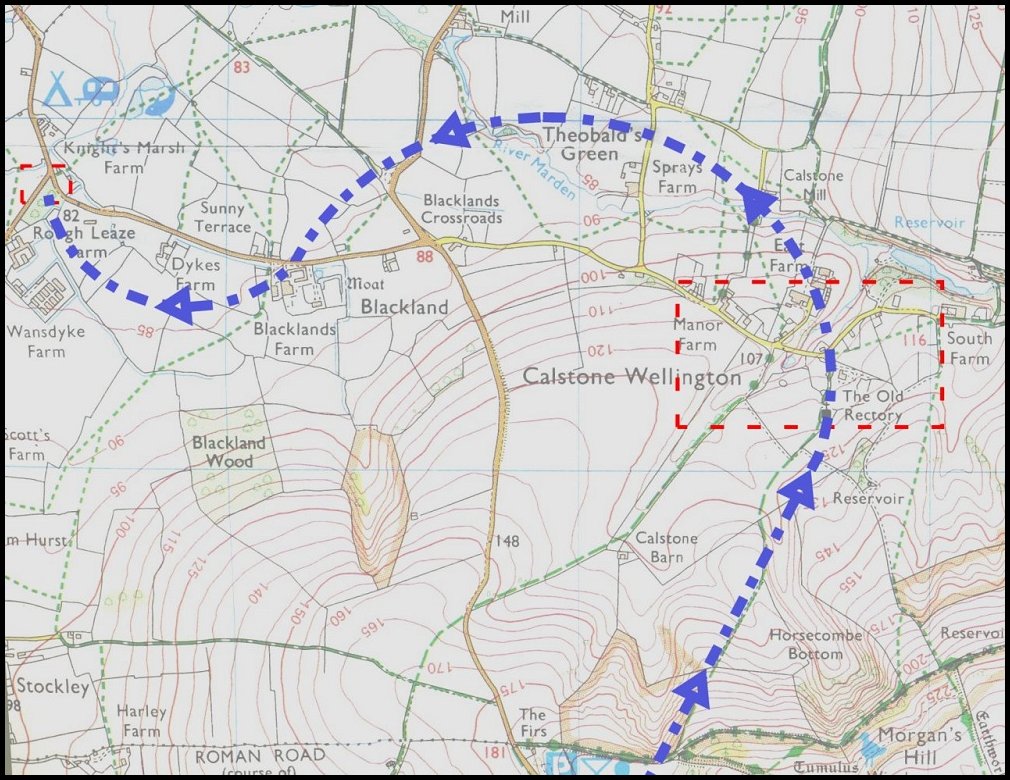

The outer wings of XA271 fell either side of the aircraft’s north-bound track on the village of Calstone Wellington in Wiltshire. The debris field measured approximately 597 yards x 337 yards. The main fuselage of the aircraft fell to earth about 1½ miles further west, in a field at Rough Leaze Farm on Stockley Lane, about 1½ miles south-southeast of the town of Calne.

Even before the aircraft had crashed, Mr Smith at Pillar Lodge on the Bowood estate had reported an aircraft in difficulties. Therefore they were already alerted when another call came in from Mrs Atwell at Rough Leaze farm to say that the aircraft had impacted the field nearby. The police, along with fire appliances from both Devizes and Calne were soon on the scene. But a fire reported in the aircraft had been extinguished when the aircraft hit the damp earth.

Meanwhile, an aircraft crash had been reported 1.3 miles further to the southwest, at Broads Green.and with no fire to attend to, the fire fighters were dispatched there. For a while it appeared that a second aircraft could have been involved. It proved to be a false alarm.

Weather at the time had the cloud base at 650 feet ASL, with poor visibility and slight drizzle. Wind measured at RAF Lyneham was 17 kt at 220 degrees.

There were a number of eyewitnesses to the accident and their statements were later recorded by the RAF Court of Enquiry team. The first witness was Mr Robert Comley of 2 Robins Place in Calstone. He was a farm worker at Manor Farm in Calstone, close to the place where the outer wings came to earth, but at the time of the accident was working further to the west at Wellington Barn. He stated that, “At 11.45 hours I heard an aircraft in the vicinity. On looking up I saw it flying in and out of cloud in a northerly direction. It appeared to be flying level. As I watched, pieces began to fall off it. I did not hear any explosion or unusual noise. The aircraft turned towards the west, flying away from me, and black smoke came from the engines on the left side. The aircraft appeared to turn on its side and dropped down out of my sight”.

The next witness was Mr Edward Dorman of 27 Theobalds Green in Calstone, who was working on a hay rick at Manor Farm at the time. He did not see the aircraft prior to its break-up, but stated that, “At about 11.45 hours I heard an explosion in the sky. I looked up and saw bits of an aircraft falling out of the cloud, followed by the aircraft itself. The aircraft was heading in a north-westerly direction. Shortly after descending out of the cloud the aircraft climbed steeply, then fell like a leaf and I saw it fall to the ground about a mile away. I did not see any smoke coming from the aircraft at any time.”

A third eyewitness was AC/2 John Luther Morgan, an Admin Orderly at No.1 Wing, RAF Compton Bassett, located about 1½ miles to the north of the crash scene. He was standing outside the No.1 Wing Mess for pay parade and was able to confirm that, “At approximately 11.55 hours I heard the sound of an aeroplane in the sky. The engine noise was so unusual that it attracted my attention and made me think that the aircraft was in difficulties. I could not see the aircraft at first but it suddenly came out of the clouds in a dive of about 45 degrees and banking slightly to the left. The aircraft was about a mile [but closer to 1½ miles] to the south heading in a south-westerly direction. The aircraft disappeared from my view behind some trees then reappeared in a steep climb. Whilst it was out of my view I heard two muffled explosions. Towards the top of its climb the aircraft vanished into the cloud. I did not see it again because my view was obstructed by buildings. During both its dive and climb the aircraft appeared to be out of control because it was rocking and weaving all the time.”

There were a number of witnesses to the later stages of the aircraft’s flight, but only one was interviewed by the RAF. He was Mr Patrick Harry James of Blacklands Farm near Calne, a building that was directly beneath the final flightpath. He was working near the farmhouse at the time and recalled that, “At about 11.50 I heard an explosion in the sky which was loud enough to be heard above the circular saw with which I was working. A few seconds later I saw a four-engined aircraft climbing very steeply with the wings outboard of the outer engines missing on both sides. The aircraft was coming towards me from the northeast and I noticed smoke coming from behind the engines, which made me think it was a jet aircraft. The aircraft then levelled out and flew straight and level for a few seconds just below the cloud base, passing over my farm. I then saw thin streams of darkish smoke coming intermittently from the outboard engines. The aircraft rocked laterally three or four times then the starboard wing dropped and it started to descend in a starboard turn. I saw it finally hit the ground descending steeply in a dive at about 45 degrees or more.”

Another person who saw the final act of this tragedy was Mr J Atwell, who lived at Roughleaze Farm, close to where the fuselage crashed to earth. He later told a press reporter, “I was working in the field with a land girl when I heard an explosion in the air. Then an aircraft came into view. It was obviously in difficulties and it looked as if parts of both wing-tips had been broken off. Smoke was coming from the wings. I thought it was going to loop the loop, then it turned sharply and dived straight into the ground a few yards from three of my horses which were grazing. They scattered in all directions. While my wife put in a 999 call, I went to the wrecked aeroplane, but it was obvious that nothing could be done.”

Some idea of the violence of the crash came from a statement made by Mrs M Clifford, who lived in the cottage just across the road. She said, “I was indoors when I heard a terrific explosion just outside, then mud spattered all over my windows. I ran out and saw the crashed aeroplane in the field in front of the house. Fortunately my children were indoors, as it was raining”.

The variations in the aircraft heading noted by some of the witnesses showed that the aircraft followed an s-shaped flight path after the separation of its outer wings.

Aftermath

The Senior Medical Officer (SMO) at nearby RAF Lyneham, Sqn Ldr Ian M Ogilvie was alerted of the accident at 11.57 am and immediately he put a team together and headed to the scene. On arrival he inspected the wreckage and located the bodies of the five-man crew. Two bodies were in the open in the immediate vicinity of the cockpit (Sgt Fowler and P Off Green), two more were found in the centre of the wreckage (Fg Off Dench and P Off Persad) and the fifth (Sgt Davies) a short distance away, beneath the tail section. The first two bodies were removed under direction of the SMO but not identified at the time. The remaining bodies were removed under the direction of the Unit Medical Officer, Flt Lt Deeman and all five were transferred to Station Sick Quarters at Lyneham, where full identification was carried out. The medical staff determined that death for all had been instantaneous, the result of severe head and other multiple injuries. There was no positive evidence that any of the crew had been strapped in.

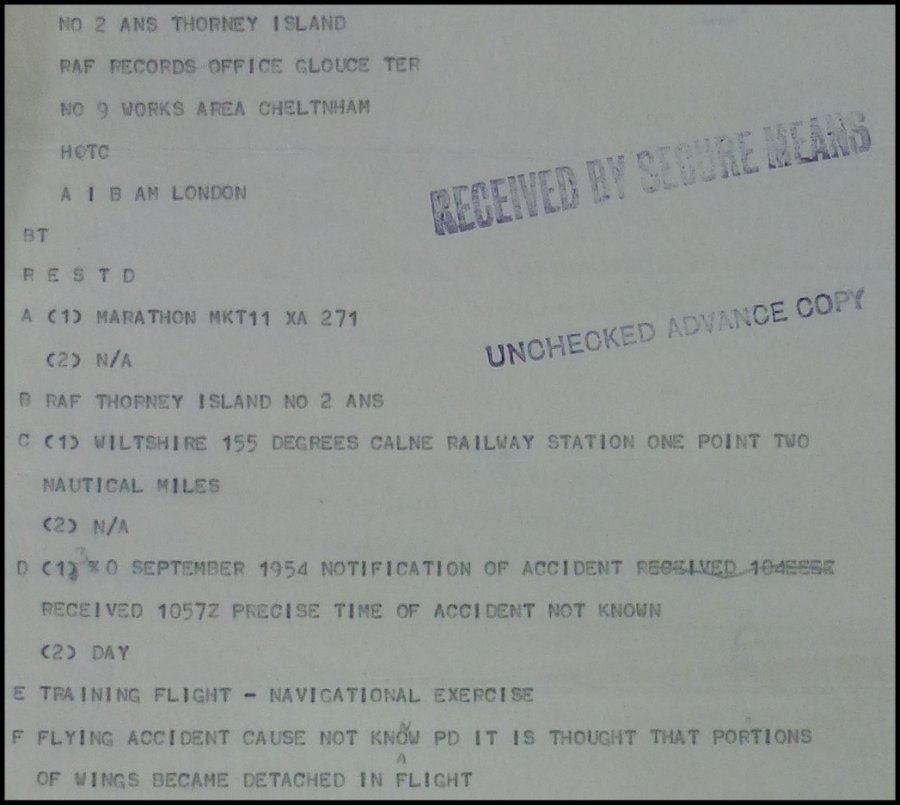

Later, at 5.10pm on the day of the accident, staff at RAF Lyneham sent a signal to involved parties (Air Ministry, HQ Training Command, HQ Flying Training Command, HQ No.21 Gp, HQ No.43 Gp, 49 MU, No.9 Works Area Cheltenham, Accidents Investigation Branch and No.2 ANS) detailing the circumstances of the accident.

Investigate the cause of the accident to Marathon XA271 which resulted in the deaths of [its crew]

1. Allocate responsibility and apportion blame if any

2. Name any recommendations considered necessary

3. Assess damage to civilian property (if any)

4. Evidence to be taken on oath.

Meanwhile, the AIB detailed the Inspector of Accidents, Mr Bertram A Morris to proceed to the scene of the accident and to assist in the Enquiry.

On the morning of 1st October the Court members began by inspecting a Marathon aircraft at Thorney Island then at 11.45 they boarded an aircraft (presumably not a Marathon!) bound for Lyneham. Unfortunately the allocated aircraft was then found to be unserviceable and following lunch they finally departed in the afternoon, arriving at 3.30pm. The Court immediately travelled to the accident site before returning to Lyneham in darkness at 8pm. The following day they returned to the crash location and interviewed eye witnesses. This process carried on throughout the weekend, the Court finally leaving Lyneham for discussions with Handling Squadron at Boscombe Down at 10.15am on Tuesday 5th October. They returned to Thorney Island later that day and then interviewed further witnesses on base during the following day. The proceedings of the Court of Enquiry were passed to the Station Adjutant at RAF Thorney Island at 11.15am on Thursday 7th October 1954.

Analysis of Wreckage

Assisted by the AIB investigator, the Court was able to state that,

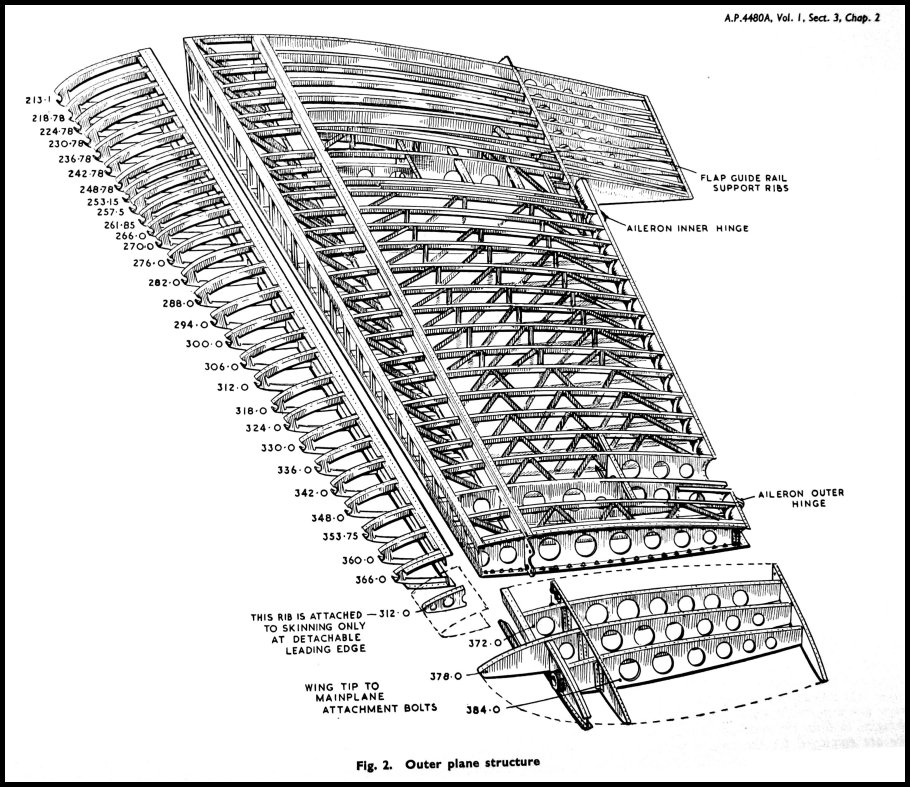

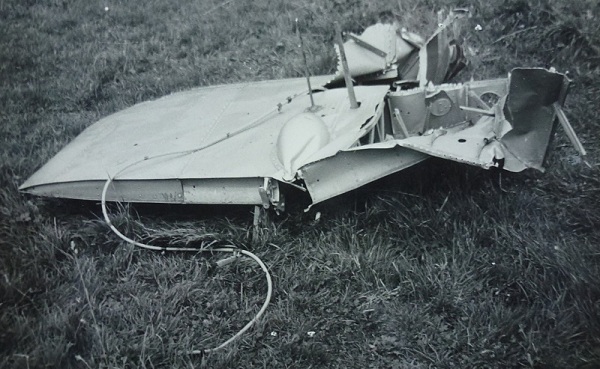

1. Both outer wings of the aircraft had broken in flight and became detached. The two wing tips broke off, each at a position nine ribs in (Rib 318), under an upload; it is probable that the primary failure occurred at this point. Breakup of the remainder of the wings from the outboard engine nacelles followed immediately. The outer wings appeared to have been subjected to fairly severe stress under positive “G” load. The major parts of the outer wings fell in a small area 350 yards by 600 yards. The remainder of the aircraft crashed one and a half miles away, hitting the ground in a very steep dive with the starboard wing down. There was no trail of wreckage or sign of fire. (The AIB inspector stated that since the failures were symmetrical on both sides of the aircraft and that the portions of wing fell close together, they were probably the primary failures).

2. The engines were buried six feet down in heavy clay. They are being dug out and removed for strip examination by the AIB. It was not considered that any positive indication would be gained from the condition of the propellers which would indicate whether the engines were under power at the moment of impact; this also is to be examined by the AIB.

3. It was not possible to establish positively the rudder and elevator trim tab settings but measurements of the actuator extensions were taken.

4. The five crew members were located in their normal positions. The state of the pilot’s harness indicated that he was not strapped in his seat.

5. The VHF frequency selected was 106.02 m/cs, that of the Flight Information Service.

6. Although the gyroscopes of the artificial horizon and of the turn and slip indicator were rotating at the time of impact. It was not possible to state positively that these instruments were working correctly. Further examination is being made by the AIB.

7. The crash damage to the pilot’s cockpit was so great that no positive indication could be gained from any of the instruments or controls.

At the time of the accident, the estimated all-up-weight was about 17,137 lb (maximum is 18,250) and the C of G position was about 34.59 inches aft of the datum (maximum aft limit is 40.1 AOD).

The AIB inspector, Mr Morris added that further and more detailed examination would be done at Croydon and following this, material tests would be carried out to ascertain their compliance with requirements. The AIB would also analyse the control trim settings (derived from measurement of the actuators) in conjunction with Handley Page. These items would be covered by a separate AIB report.

Of the witnesses interviewed at Thorney Island, Flt Lt Arthur J Owen’s statement is probably most pertinent, as it gives some colour to the bald facts otherwise mentioned. He began, “I am the Marathon Flight Commander in No.1 Squadron, RAF Thorney Island. Sgt Fowler was an intelligent, level headed and conscientious NCO, who had no particular faults. As I had been his flight commander for only one week I had not flown with him and am unable to assess his flying capabilities. On the morning of 30th September 1954, I attended briefing, in company with the other Marathon pilots who were flying on Navigation exercises. I spoke to Sgt Fowler and he appeared to be his normal cheerful self. I took off about ten minutes before Sgt Fowler, flying on the same route. On the Trowbridge to Spalding leg I flew at 5,000 feet instead of the planned 7000 feet to try and maintain VFR (visual fligh rules) conditions. I crossed Airway Green One in VFR conditions at 5000 feet. I did not encounter any bad turbulence in any of the cloud in which I flew.”

Causes

The Court of Enquiry listed the causes in its 7th October Report thus:

1. The accident was caused by a structural failure of the outer wings. From the sound of the break-up, heard by witnesses as one explosion, and the small area covered by the pieces of wing, the Court considers that both wings failed simultaneously as a result of over-stressing due to the application of positive “G”.

2. The Court was unable to determine any reasons why the aircraft should have got into such a position that the pilot had to over-stress it in recovering. The following circumstances were considered:

3. The pilot obtained a bearing from Thorney Island at 1040Z (11.40 am local), five minutes before the aircraft was seen to break up. The Navigator had done 2 minutes work on his chart since 1040Z.

4. No emergency calls were received from the aircraft, nor was the VHF on an emergency frequency.

5. The height at which the wings broke up was about 1,000 feet. The aircraft could have been visible in the broken cloud to the 5th witness (Mr Comley) at that height, and the time taken for the noise of the explosion to reach the 7th witness (AC/2 Morgan), who was about a mile away [but actually more like 1½ miles], some 5 to 6 seconds, would also indicate that it broke up at this height.

6. Comparatively light stick forces at speed can lead to over-stressing the aircraft. This fact is contained in the Pilot’s Order Book at Thorney Island.

7. The crash occurred on the southern edge of Airway Green 1. The pilot had not cleared through this airway.

8. The cloud conditions at and around 5,000 feet were changeable. It appears from the evidence that in the Calne/Lyneham area both before and after the time Sgt Fowler was approaching, an aircraft would have been in the clear, but perhaps not VFR 500 feet above the cloud tops.

9. The measurements of the rudder and elevator trim tab actuators taken at the scene of the crash were set up on another Marathon aircraft and this showed that the rudder trim setting was neutral and the elevator trim setting normal.

10. The pilot was very conscientious and had no medical history of disease or injury.

11. The freezing level was at 9,000 feet.

12. Sgt Fowler’s injuries indicated that he was in the pilot’s seat at the time of impact with the ground.

13. With the above considerations in mind the court deliberated the following possibilities:

14. The pilot lost control during a sudden descent to get under Airway Green 1, and allowed the airspeed to build up to such a figure that only a light stick force on pulling out was necessary to break off the wings.

15. The pilot performed a violent manoeuvre to avoid another aircraft resulting in a steep dive in cloud. No military or civil aircraft were in Airway Green 1 below 9,000 feet at this time.

16. There was a failure or jamming of the elevator controls. The control wires will be examined by AIB when they get the wreckage to Croydon and can open up the telescoped portion.

17. Instrument failure, causing the pilot to lose control and exceed the limits of the aircraft.

18. One or more engines failed, resulting in subsequent loss of control. It is considered that if the aircraft had been under asymmetric power it would have crashed on its initial dive and it is unlikely that the rudder trim tab would have been neutral. The Court does not consider that the engine smoke reported by two of the witnesses has any significance and was most likely caused by the pilot using his throttles in an endeavour to maintain lateral control.

19. Unaccountable illness of the pilot. This is not borne out by his medical history or by the people who knew his habits.

The Court of Enquiry was unable to apportion blame for the accident.

Recommendations

The Court seems to have settled upon just one main culprit for the accident: the light stick forces required to over-stress the aircraft. When the Court visited Boscombe Down during their investigation, they discussed the Stick Force Trials carried out on a Marathon there and discovered that at speeds above 200 kt, only very light stick forces were required to over-stress the wings to the point of failure. The A&AEE Report, submitted to the Ministry of Supply in August 1954 had recommended that the servo trim tab on the starboard elevator be fixed to increase the loading on the elevators and double the stick force required to operate them. Prior to this, on 4th January 1954, Special Flying Instruction TF597 had been issued, advising that care should be taken in the use of elevator at speeds above 165 kt because of the light stick forces and resultant ease of overstressing the aircraft. The instruction advised that, “Pending further investigation into the stick forces and any subsequent modification action, the maximum IAS is not to exceed 220 knots.”

Therefore the Court had just one recommendation: that the elevator trim tab modification be embodied without delay.

RAF Thorney Island’s Station Commander, Gp Capt SJ Marchbank was then able to consider the report and made his comments on Tuesday 12th October as follows (the emphasis is as per the original):

“After long deliberation the Court unfortunately have been unable to reach any conclusion as to the primary cause of the accident, in that they were not able to discover anything which would account for the aircraft getting into such an attitude that it was over stressed during its unsuccessful recovery.”

“In this connection although Marathon pilots are aware that stick forces for recovery at even moderate speeds are comparatively light, I do not believe it was generally realised until this accident brought the matter to the fore, that the stick forces required are abnormally light. I understand that in the region of 200-220 kt a force of 30 lbs would break the wings.”

“The basic problem with the Marathon is the unsatisfactory aft position of the C of G and modifications which do not provide a solution to what is recognised as an unsatisfactory state of affairs. The fixing of the servo control on the starboard elevator may increase the stick loadings in the top ranges, but it may also have the effect of increasing them to an unacceptable extent in the lower ranges. If the proposed modification gives satisfactory stick loadings at all speeds I strongly support it. I must stress once again however that a modification which will give the aircraft really satisfactory C of G limits is of paramount importance.”

On 9th November the Wiltshire Coroner, Mr Harold Dole presided over the inquest to ascertain the cause of death. He heard that that the wing-tips of the aircraft had come off in the air before it crashed and Sqn Ldr LAE Osbon explained that there were just eight Marathons in RAF service at that time. He went on to confirm that there was an airframe joint at the point where witnesses had seen the wings separate and that the matter was ‘perturbing’. The Coroner recorded verdicts of accidental death in an aircraft crash, due to the wing-tips coming off through a cause unascertained.

Subsequent Findings

Interim Report AI/S.2720 was issued by the AIB (Civil Aviation) on 8th December 1954. Its object was to, “…draw attention to certain undesirable features of this mark of Marathon which are considered possible contributory factors to this accident.” It was short in nature, reiterating the basic circumstances of the accident and adding more detail regarding the wing failure. In particular the AIB report was able to confirm that further examination of the wreckage had been done at Croydon and showed primary failure of each wing had been in the inboard lower skin of the outer wing where it attached to the bottom spar boom. The failure was consistent with excessive upward bending of the wings. In addition, the wing leading edge had then lifted at this point, with failure progressing outboard and transferring the up-load of the leading edge outboard until it caused tensile failure of the spar bottom boom in the region of a picketing bracket at rib 318. This damage was consistent with a high-speed pull out.

Under the heading, “Possible Contributory Factors” the AIB Report concluded as follows:

The 11th Part of Report No. A&AEE 840 Ref A&AEE/571/B2 dated 28th November 1952 states in the Summary para (b): “The values of stick force per ‘g’ during recovery from trimmed dives were lower than required by Air Publication (AP) 970 at speeds above about 160 knots indicated airspeed (IAS). In view of the possibility of structural failure resulting from the application of quite low stick forces, the elevator control should be made heavier at high speed or that the Centre of Gravity range or limiting airspeed be restricted”.

Since this was written the C of G range has not been restricted, on the contrary a further extension of the aft C of G limit has been authorized from 37.06 inches to 40.1 inches aft of datum (AOD) for gentle manoeuvres only and not for take-off or landing. It is understood however, that modification action is in hand to move certain electrical and pneumatic equipment forward in order to improve the situation and it is considered that this action should be put into effect without delay.

With reference to the A&AEE suggestion that the elevator control should be made heavier for the higher speeds, Marathon modification 1074 (Class B.2) provides for the locking of the starboard elevator servo tab and has the effect of making the elevator control heavier at higher speeds. It is understood that the embodiment brings the stick-force per ‘g’ within requirements at 200 knots (the maximum permissible diving speed is 220 knots). This modification, however, was not embodied [in XA271]. It is suggested that as its embodiment is a comparatively simple matter it should be embodied in all RAF Marathons without delay and that the maximum permitted speed be restricted to 200 knots IAS as recommended in 6th part of A&AEE/840/1 dated 23rd August 1954.

The investigation has not yet been finalised and metallurgical examination of specimens has yet to be made, although there is no visual evidence of defective material. Upon completion of this work a final report will be issued.

The metal specimens were supplied to the Metallurgy Branch at RAE Farnborough in January 1955 and comprised two pieces of 22 SWG (0.7mm) wing skins (port and starboard) to Specification DTD 610 and four lengths of spar boom to DTD 663. RAE was asked confirm that these samples taken from XA271 were up to specification. On 9th February they were able to report that the materials “amply meet the specification requirements.”

The final AIB Service Accident Report was issued on 28th February 1955. It reiterated the findings of the previous Court of Enquiry and AIB Interim Report, but expanded on earlier statements on stick force by explaining that, “The basic aircraft was designed to British Civil Airworthiness Requirements current in 1948, which do not specify a minimum value for the stick force. Flight tests have shown that at the aft C of G the stick force above 165 knots IAS is appreciably less than the minimum required by AP 970 (Design Requirements for Aeroplanes of the Royal Air Force).”

The report also was able to correct earlier reports in that the elevator had been trimmed slightly nose heavy. Full examination of the flying controls had also been completed and showed that they did not reveal any evidence of pre-crash mechanical defect or failure. The flying instruments, though broken, bore evidence of rotation at the moment of impact and there was no evidence of failure in the vacuum system or in the distribution system that supplied the electrical instruments. Strip-down of the engines and propellers also revealed no sign of pre-crash failure. The report was also able to state that the structural specimens had performed correctly.

The report’s final verdict on the crash was that, “The accident was caused by structural failure of the outer wings as a result of overstressing the aircraft in the positive ’g’ sense. This occurred during recovery action in cloud, the necessity for which cannot be determined, but may have been associated with loss of' control.” The recommendations were to embody Marathon modification 1074 on all RAF machines, to effect a move of the C of G forwards and to restrict maximum speed to 200 kt.

No specific cause for the initial loss of control was ever determined.

The Aircraft

With construction number 124, XA271 actually began life as a civilian aircraft, having been placed on the civil register as G-AMGT (Certificate of Registration No.3107) by Handley Page (Reading) Ltd on 29th December 1950. It was manufactured as a Mk.1 Marathon at Woodley in October 1951, its Certificate of Airworthiness (No.A.3107) having been issued on 17th August. On 27th October ownership transferred to the Minister of Supply and itwas then briefly stored at Woodley before being transferred for further storage at Lasham on 16th January 1952.

It was then earmarked for conversion to Marathon 103 T.Mk.11 and transferred to RAF charge on 28th March 1952, being allotted to No.5 Maintenance Unit the same day, but likely remaining in store at Lasham – the ‘5 MU’ allotment being a means of recording its change of ownership, but not location. It was cancelled from the civil register on 13th June 1952 as ‘Transferred to military’ and concyurrently given the RAF serial number XA271. On or around 27th November 1953 the aircraft returned to the Woodley production line for conversion into a navigation trainer. With conversion complete, the aircraft’s Certificate of Safety for Flight (Form 1090) was signed on 11th May 1954 and the Airworthiness Inspection Directorate released it for RAF service a week later.

Unlike most RAF Marathons, which went into storage at No.10 MU, Hullavington, XA271 was instead allotted direct from Woodley to 2 ANS at Thorney Island, the allotment taking place on 26th May 1954 and the actual ferry flight on or around the same date. The aircraft received the code letter 'A', which was painted on the aft fuselage and also in smaller size on each side of the nose section.

Its total flying time when it crashed was 351 hours and only normal servicing and maintenance had been carried out. The Gipsy Queen 172 engines were new when installed during the manufacture of the aircraft. No abnormal incidents were reported in the Maintenance Form 700.

XA271 was struck off charge in accordance with Signal AFD/43G/961/XA271/EQ on 25th October 1954.