At the start of the Marathon design process, the Miles design team considered the use of turbo-prop engines (‘airscrew turbine’ or ‘propeller turbine’ to use the terms of the day), but with this type of engine not feasible for a production aircraft at this stage, the sensible decision was made to progress with the M.60 Marathon as a piston-engined aircraft, but to design its airframe in such a way that mounting propeller turbines when they became available, would be possible. By 1946 the turboprop Marathon had been designated M.69 Marathon II (later standardised as ‘Marathon 2’) and with the increased power and reduced weight of this type of powerplant, it was envisaged to be a twin-engined aircraft.

Miles' initial design for a turbine-powered variant resulted in 'handed' engines, with each engine nacelle being asymmetric by virtue of the requirement to pass the turboprop exhaust directly aft. The knock-on effect of this was that the main landing gear would have to be offset inboard because otherwise the landing gear would be retracting directly into the path of the exhaust, which exited just below the wing leading edge. However in May 1946 GW Suggett of RDAC2(b) for Director of Research and Development (Airframes) at the Ministry of Supply (MoS) highlighted to Miles that the handing of engines was not an advantageous feature.

Suggett visited British European Airways Corporation (BEAC) on 21st June, taking with him the original Specification 18/44 and discussed the Marathon with Mr Morgan, the airline's Chief Project and Development Engineer, and Morgan re-stated their requirements (transmitted by letter from BEA to Miles on 3rd June) for the third Marathon prototype (the first two already being built with Gipsy Major engines by this date), as follows,

(a) Change engines to Armstrong-Siddeley Mamba turboprops

(b) Reversible pitch propellers are not required

(c) Retain the Miles high lift flap

(d) Nose wheel steering not required

(e) Pressurisation not required

(f) A crew of two with dual control is required

(g) Change of cabin floor to metal is agreed, provided the decrease in cost is sufficient and the increase in weight low enough to warrant it

(h) A separate entrance door for the crew is not required

(i) Miles patented fin trimming arrangements are to be retained

(j) BEAC would like to see the electrics moved forward, if possible, but will not concede any reserve

(k) Flush riveting over all the aircraft

(l) Range requirements: Full load of 650 miles with 18 passengers and baggage. Full tanks range of 800 miles with consequent reduction in payload.

It was at this meeting that the fourth prototype Marathon (which was never completed) was discussed. This machine would have featured twin Rolls-Royce Dart engines and BEA was relying on this aircraft in case the Mamba encountered any problems during its development.

Some discussion had also taken place within the Ministry of Supply, for in a 2nd August 1946 Cabinet report on Civil Aircraft Requirements, beneath the heading ‘Allocation of Design and Production Capacity’ the report boldly suggested that, “Should any conflict arise in allocating design and production capacity the Minister of Civil Aviation asks that priority should be given to…Miles Marathon II (2 propellor [sic] turbine engines)”.

Miles meanwhile began to revise the design, to the point that in September 1946 it was able to display a model of the Marathon 2 at the Radlett SBAC Show. Miles was also able to state that the aircraft would be powered by twin Armstrong-Siddeley Mamba turboprops. But any further discussion of the Marathon 2 as a production aircraft ended in April 1947 when BEAC, aware of delays in Mamba development, decided to go with the Marathon 1 instead. With no customer for the Marathon 2, the Ministry of Supply proceeded with a single prototype of the propeller turbine version to serve as a trials aircraft.

Meanwhile, though a first draft of Ministry of Supply Specification 15/46 "Civil Transport Aircraft Derived from Marathon" had been issued on 11th July 1946, it was not until 19th May 1947 (sic) that the final version was produced. The Specification was issued, "To cover the design and construction of twin-engined civil transport for day and night operation by the British European Airways Corporation, derived from the Marathon aircraft to Specification 18/44". Mindful of the cancellation of the BEAC order just one month prior to the issue of the finalised specification, it would appear that this was a simple tidying-up exercise, for by this time the Marathon 2 was well advanced in its production, and it was well-known that there was no customer for it. It is of course also possible that the MoS was hoping for BEAC to reverse its decision, but this never happened.

The Specification was for a Marathon powered by two Mamba engines but the use of Rolls-Royce Darts was an option. Cruising speed was to be 210 kt (389km/h) at 10,000 ft (3048m) with a range of 565 nautical miles (909km). The Marathon 2 was to carry 3,870 lb (1755kg) of payload, which broke down into eighteen passengers (170 lb/77kg each) and 45 lb (20kg) each of luggage.

Meanwhile, the MoS had issued Requisition No.42/47 to Miles Aircraft Ltd for, "Diversion of Production Marathon Mk.I for conversion to prototype Marathon Mk.II for Mamba development work." At Woodley, the Marathon II (Miles type M.69) would be the third Marathon built and was allotted the construction number 6544. It was registered as G-AHXU on 10th July 1946. Miles was issued a Contract Instruction in April 1948 to change this aircraft to the miliary serial number VX231 but this change did not happen until several years later.

The Marathon 2 was designed so that the Mamba turboprops were mounted on what would have been the inboard engine mounts of the piston-engined Marathon I. The Mamba developed just over 1,000 hp and 300 lb (136kg) of thrust was also provided by the exhaust. The twin-engine layout freed up space within the wing for additional fuel and an extra 70 gallon (318 litre) tank was installed in each wing as a result. To test the aerodynamic effects this installation would have, Miles constructed a 5/6th scale plywood nacelle and it was flight tested on the prototype Aerovan.

Sadly, the development of this aircraft coincided with Miles being forced into receivership during 1947/48. The Mamba Marathon was well advanced on the Woodley production line and would have flown in the spring of 1948. But that year came and went, and when Flight magazine visited Woodley in May 1949, their reporter was able to give a technical update on the prototype Marathon 2,

“On the Gipsy Queen-engined Marathon the rear ends of the four nacelles house the sizeable guide-rails and operating mechanism for the flaps. In the case of the Marathon 2, small so-called dummy nacelles are fitted to fair off this flap gear. It has been suggested that as these dummy nacelles must be fitted, they might be enlarged to full drop-tank proportions in order to be able to carry more kerosene for the Mambas, wing space for the tanks being rather restricted.

The Mamba-powered Marathon 2 at Woodley in July 1949.

Among the various modifications necessary for installation of turboprops is the strengthening of the tailplane and fins. The jet pipes discharge over these surfaces but, as the efflux is very small, ill-effects are improbable. Although the Marathon 2 appears well advanced, a great deal of detail equipment, including the engine controls, has to be looked after, and certain items are in short supply. The experimental section will have to work very hard to complete the aircraft in time for it to fly and appear at this year's SBAC display.”

|

The Armstrong-Siddeley Mamba In mid-1945 the Armstrong-Siddeley engine company received a contract for a turboprop in the 1,000-hp class. Under technical director Bill Saxton and chief designer A Thomas, design of this engine was rapid, and now known as the Mamba, the first prototype ran in April 1946. By September of that year the engine had achieved its 1,000 hp target and a 500-hour sealed-test run was completed in 1948. The Mamba featured a 10-stage axial compressor, supplying air to six combustion chamber cans and then to a two-stage power turbine section. Fuel combustion was achieved by a novel system of pre-heating it by passing combustion heat over the delivery pipes. Armstrong Siddeley claimed that this enabled the combustion to be controlled across a wide range of temperatures and pressures, and lower fuel pressures meant that burner design was less critical. The power turbine drove a 10 ft diameter, 3-blade propeller via a reduction gearbox, which was mounted in a neat spinner fairing. The engine measured just 27 inches (686mm) in diameter when fitted into its streamlined cowling and represented a massive 70% reduction in frontal area when compared to a piston engine of similar power. Dry weight was 750 lb (340kg), or 75% the weight of a comparable piston engine. When developed for production the engine was rated at 1,010 hp (Armstrong Siddeley advertised 1,120 hp) and provided 307 lb (139kg) of thrust from its exhaust at 14,500 rpm. At Economical Cruising Power (13,750 rpm) the engine developed 747 hp and 265 lb (120kg) of additional thrust. At this setting the engine consumed 79 gallons (359 litres) of fuel per hour. The engine was seen as a strong competitor to the Rolls-Royce Dart, but whereas the Dart found a place in aircraft that gained large production contracts (notably in the Vickers Viscount), the Mamba did not. Aside from the Marathon, the engine was trial-fitted in a Dakota and was standard equipment on the Armstrong-Whitworth AW-55, Avro Athena T.1, Boulton-Paul Balliol T.1, Breguet Vultur and Short Seamew. Only the Seamew (with just 26 aircraft built) could be described as a production type. It was only when paired core engines were coupled to drive contra-rotating propellers that (as the Double Mamba) it found success. It saw many years of reliable service in the Fairey Gannet naval aircraft.

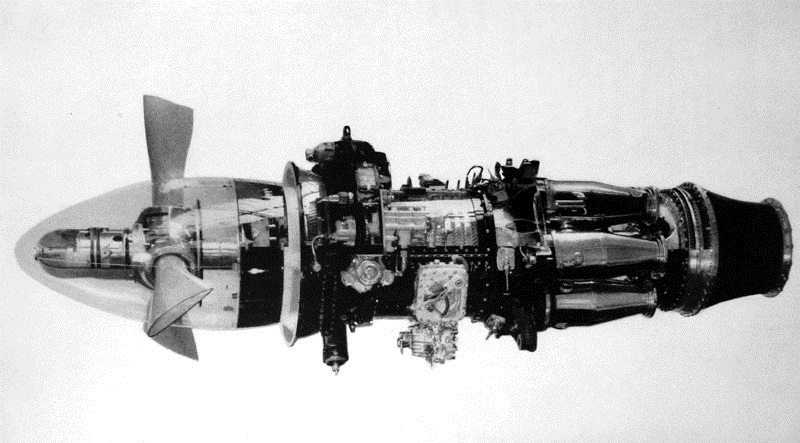

An early Mamba engine with propeller boss and dummy spinner installed. |

G-AHXU finally flew on 23rd July 1949, with Hugh Kendall as pilot. Performance was found to be better than the Marathon 1 and with eighteen passengers and 540 lb (245kg) of luggage, the Mk.2 would have a range of 770 miles (1239km) at 260 mph, against 500 miles (805km) at 175 mph for the Mk.1. If range was limited to 500 miles, the Mamba-engined Marathon could carry 22 passengers and 1,000 lb (454kg) of luggage and arranged as a freighter it had more than 1,000 cubic feet of cargo space and could carry 5,470 lb (2481kg) for 500 miles or 4,370 lb (1982kg) for 770 miles. Normal cruising at 260 mph would be at 10,000 feet (3048m), with a service ceiling of 35,000 feet (10668m). At an 18,000 lb (8165kg) all-up weight, takeoff run was 700 yards (640m) and initial climb was 2,100 ft/min (640m/min). Lightly-loaded at 13,000 lb (5987kg) the run was just 300 yards (274m) with a climb-out at 3,000 ft/min (914m/min).

The Marathon 2 was loaned to Handley Page for exhibition at the Farnborough SBAC show from 6th to 11th September 1949. Flight reported that, “There could be no objection to the subdued note of the Marathon II's 1,000 hp Mambas as they lifted this experimental, so far unfurnished, feeder liner off the runway—or during the brief take-off run (700 yds fully laden) which preceded its startlingly rapid climb. Overhead, Hugh Kendall feathered one airscrew and gave convincing evidence of the Marathon's excellent handling qualities and half-power performance, both on the climb and in near-silent, flaps-down flight at low throttle.”

In March 1950 the aircraft was sent to the A&AEE for acceptance trials and during August of that year it was loaned back to HPR to compete in the Daily Express South Coast Handicap air race the following month. The race took place on 16th September, 1950, Sixty-seven aircraft leaving Bournemouth’s Hurn airport for the 200.6-mile sprint eastwards to Herne Bay in Kent. Organized by the Royal Aero Club on behalf of the Daily Express, there were a number of interesting starters, including the Hawker Hurricane PZ865, piloted by Mr F Murphy (who finished 21st) and George Miles himself in an Aerovan. He finished in 14th. The eventual winner was Mr NW Charlton in a Percival Proctor 1, who completed the course in 1 hour, 44 minutes and 1 second. Hugh Kendall brought the Mamba Marathon home in 7th place, with a time of 1 hour, 44 minutes and 45 seconds. He was thereby placed 1st in the Unlimited class.

G-AHXU was then loaned to Handley Page for participation in the 1950 Farnborough SBAC display for the period 3rd to 11th September. This time the aircraft was displayed in the static park and did not fly. It was equipped with four observers seats in the main cabin, along with ballast boxes.

In February 1951, the Marathon 2 was allotted to de Havilland Propellers for Mamba airscrew development and for the investigation of control problems. The aircraft was ferried from Reading to the company at Hatfield on 29th March. Thereafter the aircraft remained at de Havilland on propeller work and its military serial VX231 was finally applied on 29th May 1951, The Marathon 2 retained this marking through the rest of its flying career.

The aircraft was again loaned to Handley Page for the SBAC Show in 1951 and shortly after its return to de Havilland, on 2nd October 1951 it suffered an unspecified accident and it is not known if it underwent any further testing work at this time. It was then planned to place the aircraft with the Empire Test Pilots School at Boscombe Down for instruction in turbo-prop handling, and VX231 was ferried to Reading by air from Hatfield on 16th October 1952 so that HPR could perform an overhaul. Pending approval it was placed into storage with just 66 flying hours on its airframe. But by January 1953, the Director of Research and Development (Airframes) at the Ministry of Supply had begun to raise concerns that the aircraft could be better employed elsewhere. Since few spares had been provisioned for the Mamba Marathon, and with early-standard engines which were prone to stalling, it was thought that the Armstrong Whitworth Apollo would be better for ETPS use. Miles had yet to begin the overhaul (based on a quote of £2,250 and a 12-week schedule) and Director of R&D (Engines) had already suggested that the unique aircraft would be better-suited as a twin-engine testbed for the Leonides Major and so an abrupt about-turn was performed. On 12th March 1953 it was decided to send the 2nd prototype Apollo to Boscombe Down and allot the Marathon 2 for Leonides Major development work.

Marathon 2 Data (Two 1,010 hp Armstrong Siddeley Mamba)

| Span | 65 ft |

| Length | 52 ft 3 in |

| Height | 14 ft |

| Wing Area | 500 sq ft |

| Aspect Ratio | 8 ft 4 in |

| Aerofoil Section | NACA 23018 at root, NACA 23009 at tip |

| Weight Empty | 10,850 Ib |

| All up Weight | 18,000 Ib |

| Wing Loading | 36 lb/sq ft |

| Maximum Speed | 290 mph |

| Cruising Speed | 260 mph |

| Rate of Climb | 2,100 ft/min |

| Rate of Climb (single engine) | 700 ft/min |

| Time to 10,000 ft | 5 min |

| Range | 900 miles |

| Duration | 3½ hr |

VX231 was allotted to Handley Page at Woodley on 8th June 1953 for the Leonides Major conversion work to begin. Specifically the aircraft was detailed for, “Flight development of Alvis Leonides Major engine fixed-wing applications against Contract 6/Acft/9565/CB10(b)”. Therefore, in a rather retrograde step, the clean-cowled Mamba turboprop engines were removed and replaced by much more bulky radial engines. It was somewhat ironic that this product of the Miles company would be testing the engines projected for the Handley Page Herald, a design which also started life as Miles project.

Now under Alvis power, the re-engined Marathon 2 was first flown with Leonides Major engines on 15th March 1955. The pilot was Sqn Ldr HG Hazelden, Handley Page’s chief test pilot. After a short period of flight trials at Handley Page, VX231 was handed over to Alvis at Coventry’s Baginton airfield on 5th May 1955, where the company’s test pilot John Williams did the development flights.

The aircraft was only at Coventry a short time, for on 28th May it was returned to HPR for unspecified rectification of its undercarriage doors. It was returned to Alvis by air on 10th June and after a short period of trials the engines (s/n 7 and 9) received a 25-hour examination, the inspection report dated 21st June stating that, "Intrascope inspection of the supercharger guide vanes has shown acceptable results; there does not appear to be any serious cracking. In addition the crankcase inspections show the cases to be sound. More detailed inspection of these features would entail removal and part strip of the engines with reultant proof runs etc, all of which would take a month to complete according to Messrs Varney and Hancock". The test team were confident with the state of the engines and so a further 25 hours of flight running was authorised, subject to between-flight oil checks, daily crankcase inspection and inspection of the supercharger guide vanes every 5 hours.

VX231 spent a further period with Handley page from 2nd to 13th September 1955, this time for modification to the wing structure. It then seems to have served Alvis very well for the next few years, on a series of short-term loans from the Ministry of Supply, and all the while wearing its military serial number and roundels.

The staff of Flight magazine visited Alvis in September 1955, and were able to report that the engine had completed 3,000 hours of bench and airborne testing; stiffening of the cam ring had enabled the Leonides Major to progress towards type-testing at the designed minimum of 850 hp. By this time the Marathon 2 had flown 140 hours and was being used to complete 250 engine hours as quickly as possible so that a ‘time between overhaul’ period – initially at 250 hours but hoped to rise up towards 400 hours – could be established. It was hoped that Leonides Major-engined HPR Herald aircraft would eventually reach TBO periods of 600 hours. The Flight reporter went on to detail the technical side of the engine installation,

“The test-bed nacelles are, of course, identical with those of the Herald, and it was clear that cooling and other items which are generally a function of the installation are all satisfactory. The cowling gills are electrically operated and oil temperatures can be easily controlled by them.

In this first test-bed no particular effort has been made to relate the throttle movement exactly to power response—nor is any great alteration absolutely necessary. Response is a little slow over the lower range of throttle movement. The engines are, however, very smooth and quiet and give a most pleasant ride.

The de Havilland three-bladed, constant-speed, feathering airscrews are a slight modification of a standard pattern and will shortly also be fully type-tested.”

VX231 was eventually sold to Armstrong-Siddeley Motors on 23rd June 1958 against sales contract JT/219/083/D3(a), but was scrapped at Bitteswell in October of the following year.

|

The Alvis Leonides Major The Alvis Leonides Major was a 14-cylinder, two-row radial, air-cooled engine with supercharging and reduction gearing. The engine began its development in 1951, based upon the 9-cylinder Leonides radial. It was designed in two applications – the 702/1 for fixed-wing aircraft and the 751/1 for helicopters at 850 hp. These engines had previously been designated A.Le.M 1-1 and A.Le.M 1-2, respectively. The 702/1 engine was built around a 3-piece aluminium crankcase, onto which the steel cylinder barrels were bolted. These in turn carried aluminium cylinder heads with one inlet and one exhaust valve. The crankshaft was supported in three roller bearings and at is forward end a reduction gear reduced engine speed at the ratio of 0.533:1. Provision was made for fitting a Rotol No.4 propeller, but on the Marathon installation, de Havilland 3-blade items were installed. The supercharger was a single-speed type, gear driven off the back of the engine and giving a compression ratio of 6.5:1. It was fed by a single Hobson AL6 updraft injection-type carburettor, directing fuel into the eye of the supercharger impeller. The Leonides Major 702/1 displaced 18.3 litres and was 38.9 inches (988 mm) in diameter and 70.9 inches (1800 mm) long, for a weight of 1200 lb (545 kg). It derived 875 hp at take-off and 500 hp cruising at 2600 rpm and 11,000 ft (3350 m). Like the Armstrong-Siddeley Mamba, which was also fitted in the Marathon 2, the Alvis Leonides Major didn’t find great success. Originally planned for the four-engine Handley Page HPR.3 Herald (one prototype), this aircraft was soon developed into the twin-turboprop HPR.7 Dart Herald and the Leonides Major thereby lost its single fixed-wing application. Helicopter versions of the powerplant fared slightly better, powering various iterations of the Bristol Type 173 and also some versions of the Westland Whirlwind.

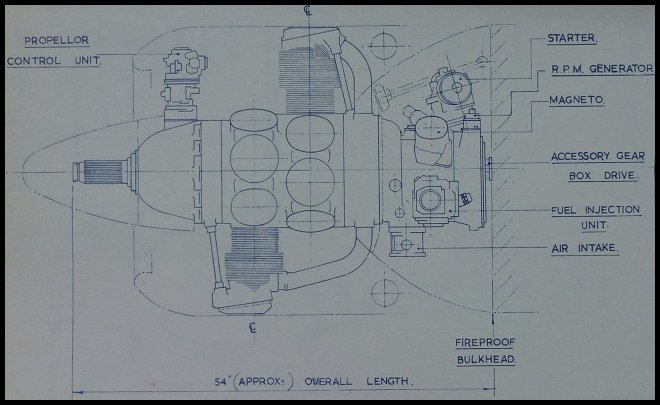

Alvis Leonides 702/1 fixed-wing engine. |